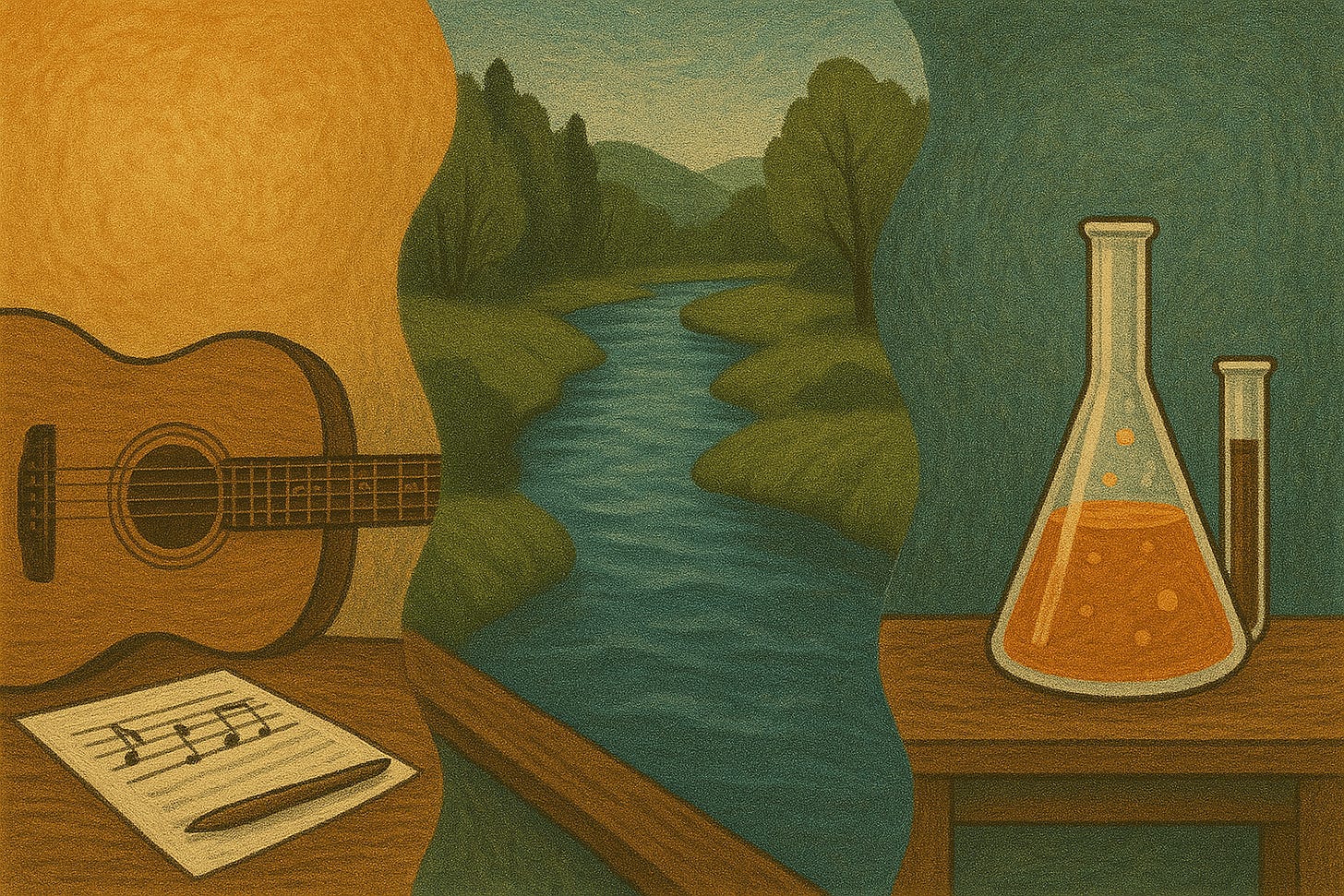

Yes - I recorded an album

On music, science, and being your honest self

Music was there from the beginning. The stacks of old 1960s records from Mom, country radio with Dad, and my brother and sister who collectively introduced me to nearly every obscure band of the 80s and early 90s - King Missile, Teenage Fanclub, or the Smithereens, anyone? In the last blog, I even reminisced about how record shops were a major part of my early experience with art and a well of insight into ideas that refuse to die. When I was 15, I began learning guitar, and almost immediately, also started writing songs. Few songs from these early days were any good, but that creative process became an important channel through which I processed emotions during those confusing adolescent years. And I suppose I’ve also always been a bit of an interior person, who for better or worse (mostly worse), tends to bottle things up. It was music, therefore, that was there when I struggled through those early relationships, when my Dad passed when I was 23, and when I worked through the classic patterns of rejection that are so common along the early academic path.

As I got older, writing songs and playing music became less something to pursue seriously, but something I still enjoyed nonetheless. There remained an undeniable catharsis and pleasure to writing and playing songs. And so I went on, scribbling words and arrangements sporadically into notebooks stashed behind my guitar amplifier, upon which there was also a pile of peer-reviewed science articles. From the time I started my first faculty job to today (~15 years), I wrote somewhere around 30 songs, mostly when the stars aligned, meaning the mood caught me just right, and there was some time with no screaming kids, or brush fires to stamp out at work. Only about a dozen of these were decent enough that I would ever play them again. Occasionally, I had the foresight to set up a Shure SM58 microphone and record some rough cuts.

Over time, those scattered recordings became a kind of diary: a record of who I was and what I was thinking between all the science papers, life changes and cross-country moves. Some months ago, I played a few of the cuts for a friend, and they encouraged me to put them out somewhere. It had been awhile since I watched anyone listen to my music - that felt good. So I decided it was time to send it out into the universe. Talking to the Stars is the collection of songs recorded in this haphazard way over these years. It is the art I was making, while at the same time pursuing my dreams in science. These songs were written and recorded in all kinds of places and times over that period. Walking Lonely American Blues and Johnny B. Goode were recorded on an iPhone 4s in the basement of our house in Virginia. Cooler Days and Backstreets were done in Wisconsin - one at our rental house in Madison, and the other in the living room of my family's cabin in North Wisconsin. Dry Bones, Ballad of a Southern Evolution, Bleed4u and Skyscraper were all recorded in California, although only Dry Bones was written out there. Attic Song is the oldest and was recorded during my grad school days in the attic of an old house in Auburn AL, one that has since been bulldozed. It is odd to describe these songs in the following way, but they were 100% no AI; I’m not sure that will be the case for many songs going forward anymore. So, these songs cover a lot of ground in my life, and in a way, are a bit of a proof that the science and art had never really been totally separate and independent pursuits.

The Science-Art Connection

Most scientists I know tend to also love music. We do lab work with earbuds in. We write manuscripts for peer-review to background music that promotes deep work. Sometimes, we even sing or hum a tune while conducting field work. This is a great thing, and I think it also says something about the underappreciated alchemy that exists between art and the sciences already.

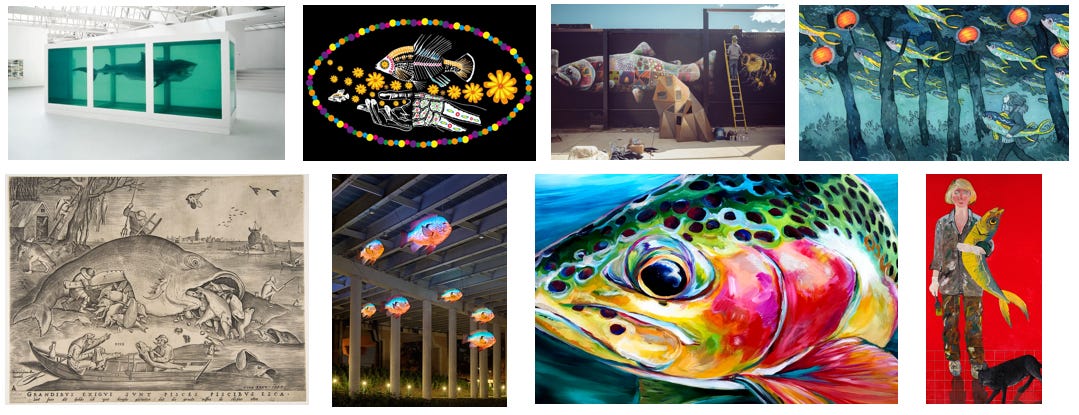

For years, I taught a large ichthyology (biology and evolution of fishes) class. The class was >200 students, and the first lecture was always a bit gauche. The audience was always so cold, mostly because they don’t know you at all. I would then mention that before launching into each lecture, I would show them some fish art, usually pertaining to the lecture topic of the day. Almost immediately, the hard faces would soften and the mood would lift. There was also an extra credit project where students could create their own fish art and/or haiku, if they wanted. Admittedly, these activities were a bit of a gimmick, but an effective one I learned from a great mentor, Peter B. Moyle. The art captured their attention, and suckered them (pardon the pun) into spending more time thinking about fishes. As time wore on though, class alumni often told me how the fish art (Fig. 1) was something they genuinely enjoyed, and that few other science professors ever talked about art. Some of the students were truly exceptional artists, and then I watched as they launched impressive careers in STEM. Creative students often turned out to be great at science too. I’m not the first to make these observations either. EO Wilson, in a controversial op ed, discussed how we often steer creatives away from STEM by sending the message that you must be good at math to also be good at science.

In my own life, I’ve wondered over the years, about the extent to which the music and science fed from one another. Was the music distraction from the hard science? Was it mutualistic with it somehow? Or perhaps scarier, was science a distraction from the music? Now, with many years of doing both (admittedly with my focus primarily on the science) I think I have a better understanding and a willingness to share more.

Our brains are extremely sensitive to art, but these connections are underappreciated and misunderstood. In the recent book Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us, the authors demystify much of this impressive science. Apparently, most of what our brains do occurs below awareness, in response to a constant river of sensory input. Because art is so sensory, it taps into the brain’s wiring. In particular, neuroplasticity, i.e., our brain’s ability to form new neuronal connections in response to experiences, is a central part of the story. Contrary to the long-held belief that our brains cannot grow or change - they definitely can and do - primarily through rewiring. Decades ago, in a striking set of experiments in a mouse model, neuroscientist Marian Diamond showed that mice living within enriched environments (analogous to art-rich environments) literally grew a thicker brain cortex compared to controls. When we experience powerful things like art, our nervous system begins release of a cascade of neurochemicals designed to help etch these experience into our working memory. It’s our brains evolved way of saying “more of this”. Multiple regions of the brain collaborate to decide which moments are significant enough to warrant such a reaction. However, music, art and other intensely aesthetic experiences are key drivers, pulling into motion the very systems that also control memories and meaning. The growing body of evidence therefore makes one thing clear: beauty, art, and nature aren’t luxuries. These are essential nutrients vital to the nourishment of a healthy brain.

At its root, science is a business of ideas. It is a creative endeavor, just as too is art. As I discussed in the last blog, it can help scientists to think of themselves as mental athletes. Staying in mental shape necessitates exercising your brain, feeding it the right things, and growing the capacity to generate and develop ideas that last. Certainly reading books, being surrounded by other mental athletes, and spending time on your craft everyday helps. However, so too is exposing your mind to new ways of thinking, and other ways of knowing. Robert Sapolsky makes some important observations in his classic essay ‘Open Season’. For example, he recounts the work of the psychologist Dean Keith Simonton who found that creativity and openness in great thinkers does not actually decline with age, but with the length of time spent in a single field. Those who switch disciplines often experience a renewal of openness. In other words, it’s not chronological age that matters most, but disciplinary age. Art, music and creative pursuits are additional fields of study - other ways of knowing. Therefore, the mental athlete is benefited directly by the essential nutrients of art described above, but also, indirectly by the switch in disciplinary thinking.

There are surprising examples of scientists who crossed over into the arts. Leonardo da Vinci is the archetype of the artist-scientist. Beatrix Potter is best known as a children’s author, but she was a serious mycologist and naturalist whose watercolors of fungi were published in peer-reviewed journals. During the 1960s, near when he won the Nobel Prize, the great theoretical physicist Richard Feynman began drawing seriously, studying under artist Jirayr Zorthian in Pasadena CA. Feynman’s art spanned studies of the human body, portraits of friends, playful sketches, and abstract explorations of line and form.

Beyond cognitive benefits, it’s morally right to ensure people have agency to live their lives as their honest selves. I worry about this for the next generation. It is sad that we are all watched now, a bit like tagged animals. And I see it often where young scientists feel compelled to pretend that they are only their jobs. Anything less, is to convey an image of someone who is undedicated to the one true mission in some way. Social media does us no favors in this regard, as it encourages people to cultivate images and personas - avatars of themselves - that they believe others will approve of. This can’t be healthy. Perhaps it is for these reasons that apps like Soul (an anonymous social media app) are increasingly popular. I kind of get it too. Indeed, I think that for many years, science trained people to hyper-fixate exclusively on science, and to push down anything that didn’t conform. Any distraction would be perceived as an indication that one wasn’t serious enough about their hard science. Perhaps this is partly why Feynman himself signed his own drawings under the pseudonym “Ofey”. The problem is that when we hide our true selves, it goes subterfuge, and then manifests in unhealthy ways. Besides, why are we trying to make people conform in the first place?

The culture of openness within STEM is better now than it was, but there is still stigma. As a leader in higher education myself now, it is important for me to show and articulate to others what I truly think. I am not afraid to be my honest self, certainly to you all readers, but also to the people who I lead. People deserve genuine leaders who are their true selves and will tell others what they actually think, even if that something is difficult or unexpected. In my opinion, being your honest self is a prerequisite to asking for and gaining trust from others. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.”

Without question, I know now that working on the craft of songwriting all those years changed my brain in certain ways. And I do credit it with some of my abilities to be creative in science, and to write in interesting ways. In retrospect, it was probably a huge gift that songwriting came to me as young as it did. So, I want to conclude this blog by simply encouraging all of you, especially those with artistic and creative habits. Don’t give these awesome aspects of yourself up for an avatar of what you think others will approve of. For those of you that are creative and never considered science before, give it a shot! I think you might be energized by the capacity of science to allow you to be creative. Indeed, the future is exciting, because the evidence is finally showing us just how powerful the arts can be for our brains. It is not just a pleasant distraction, art actually makes you smarter and provides a more enriched life. I am excited to see how in the future we might merge mindsets further, not only to enjoy our time on Earth, but to solve really challenging problems.

Go Deeper

Magsamen, S., and I. Ross. Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us. Random House.

Rypel, A.L. 2025. In defense of ideas with a long half life: feed your brain what matters. Tangled Nature https://tnature.substack.com/p/in-defense-of-ideas-with-a-long-half

Sapolosky, R.M. 1998. Open Season: When do we lose our taste for the new? The New Yorker https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/03/30/open-season-2

Wilson, E.O. 2013. Great Scientist ≠ Good at Math. The Wall Street Journal https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323611604578398943650327184?reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink

https://www.themarginalian.org/2013/01/17/richard-feynman-ofey-sketches-drawings/

https://restofworld.org/2022/3-minutes-with-zhang-lu-soul/

Listen to Talking to the Stars (links to multiple platforms below):

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_lZCDiPuP0ayZWfcCZ_sdTQAo1ggaZIXGk