America's Ghost Lake

“Monsters are real, and ghosts are real too. They live inside us, and sometimes, they win.” ~Stephen King

Ghosts don’t always appear in white bedsheets or campfire tales to scare kids. Some are ecosystems from the past that refuse to stay gone. They are the ones we did away with, or tried to. They appear to us decades or even centuries later, often as patterns we don’t recognize - because while our forebearers knew these places well, we just don't. Yet those who’ve lived in one of these landscapes, and learned the history, know the ghosts. They know something is still there, even if it’s been gone for a long time.

In California’s Central Valley, the ghost is a large lake - Tulare Lake.

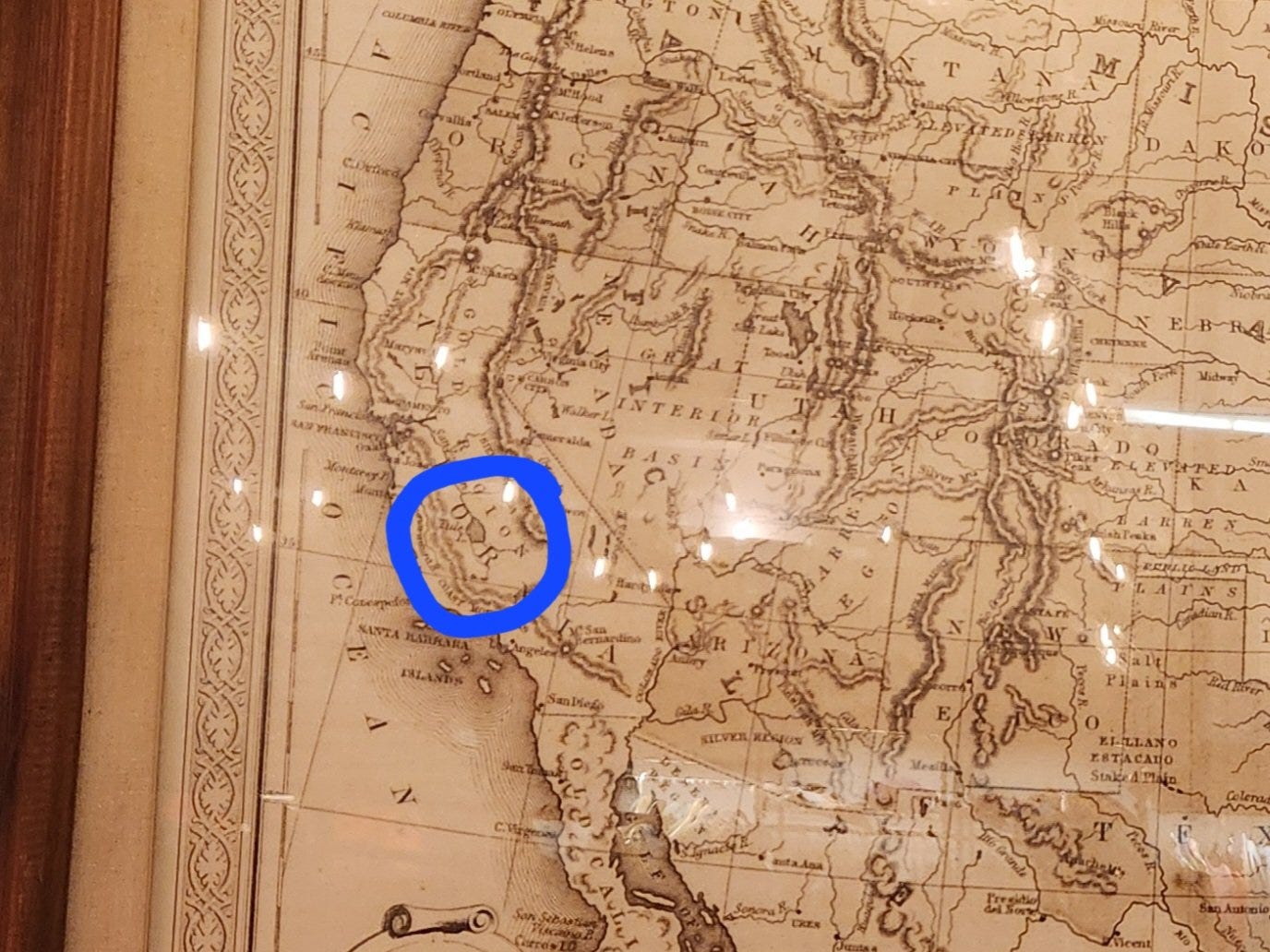

As recently as 200 years ago, Tulare Lake (Yokuts: Pah-áh-su, Pah-áh-sē) was the largest freshwater lake by area west of the Mississippi River (75 miles long and 45 miles wide). Fed by the Kern, Tule, Kaweah, and Kings Rivers, the lake was so ginormous you could have taken a boat from Bakersfield to Stockton. Beneath its extraordinarily productive soils lay a thick, impermeable clay (aka ‘Corcoran Clay’) which causes water to pool in the lakebed. Shallow and without a permanent outlet, the lake’s footprint expanded and contracted dramatically with California’s wet and dry cycles.

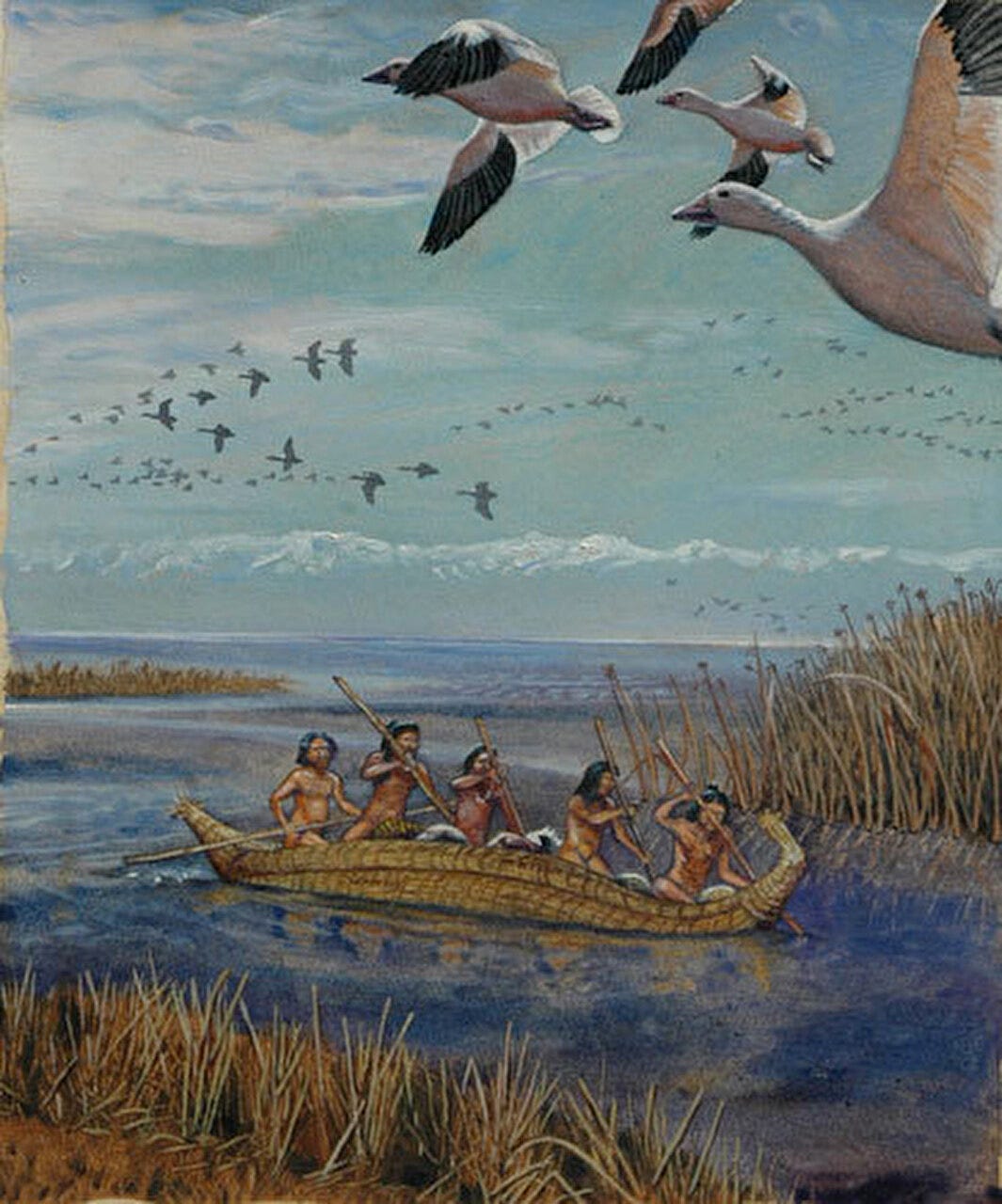

Indigenous peoples lived all around the lake, by many accounts, the largest population centers north of Mexico. The landscape was both beautiful and productive: tule marshes, abundant native fishes, immense flocks of waterfowl, turtles, tule elk, and bears.

What a sight it must have been.

By all accounts, the bird populations were immense, and Tulare Lake was a major hub of the Pacific Flyway. For a time, the finest restaurants in San Francisco served Tulare Lake terrapin (Arax and Wartzman 2005). The last grizzly bear killed in California was shot in Tulare County, California in 1922.

Tulare Lake itself is a remnant of something even more ancient: Lake Corcoran, which covered much of the Central Valley roughly 665,000–758,000 years ago. That waterbody was an inland sea the size of Lake Michigan. Tectonic shifts eventually opened the Carquinez Strait, draining Corcoran into what became San Francisco Bay. Tulare Lake is what remains.

For millennia, Tulare Lake did exactly what it was made to do. Water slowed down here. It spread, retreated, grew bugs, attracted birds, and supported the abundant animal and plant life of the area in spades. Nutrients accumulated. Life multiplied. This wasn’t wasted space. It was a garden of Eden, in inland southern California.

That, however, became the problem.

Draining a lake that worked too well

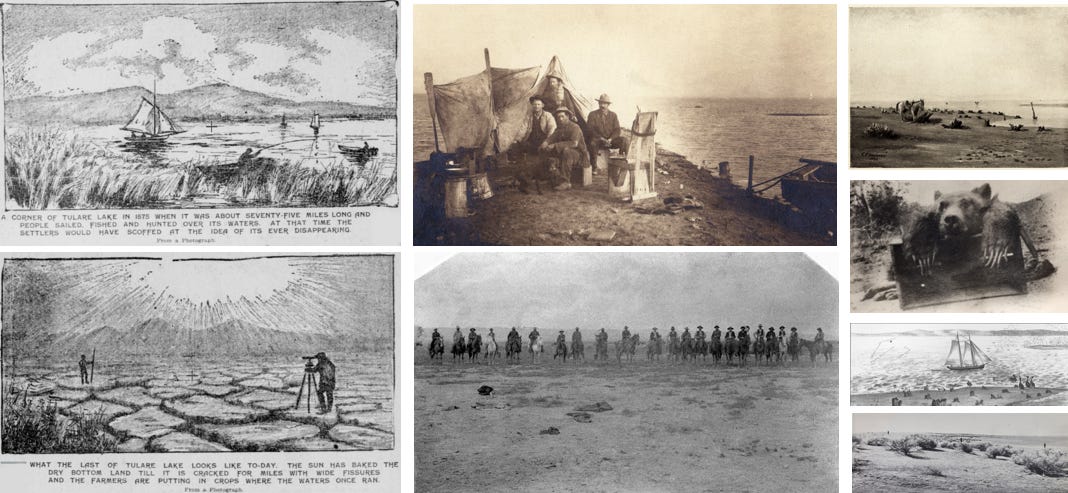

To settlers arriving in the Central Valley, a massive lake that contracted and expanded wildly at will, beyond fences and property lines, was NOT okay. Local historian and newspaper columnist F. F. Latta wrote that powerful Valley winds could redraw Tulare Lake’s shoreline by as much as five miles in a matter of hours. Flooding posed serious challenges with real consequences for livelihoods.

The prevailing water management paradigm at the time was to master water through engineering (Rypel 2025). No court was to be given for natural hydrologic processes. And really, who could resist the promise of secured prosperity? The soil is amazingly fertile here, and the climate highly conducive to agriculture. You just need to add water. California’s San Joaquin Valley could be a gigantic greenhouse for America.

And that's exactly what happened. Rivers were straightened. Channels cut. Levees rose where shorelines once flourished. A labyrinth of pumps and pipes installed, the scope of which will still impress most any engineer. The lake was not killed through a single act, but slowly and methodically. It was reduced year-by-year, flood-by-flood, eventually, into hydrologic domination.

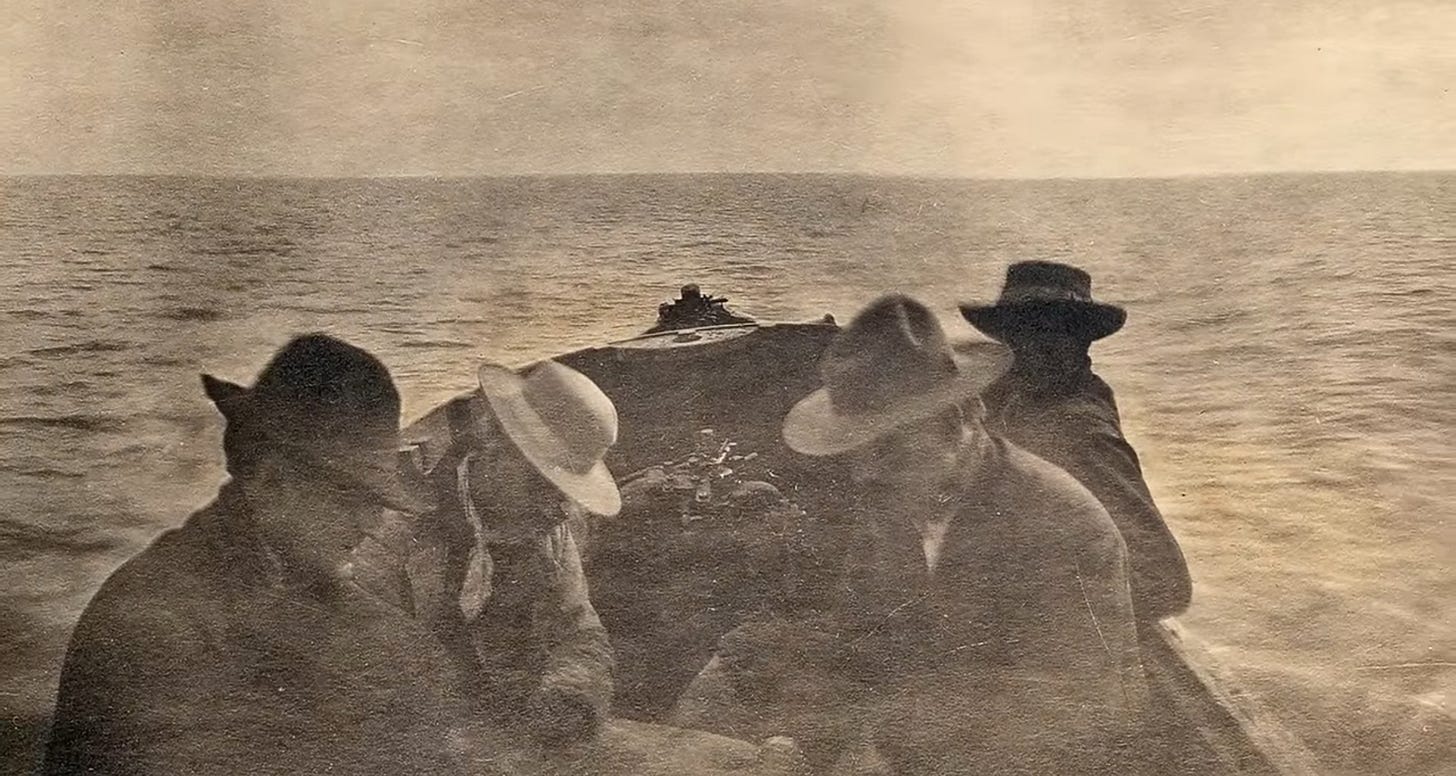

“This lake was a lifeform. You know, this lake, it talked to us, and we talked back to it. And we understood what it wanted, and it understood what we wanted.” ~Robert Jeff, Vice Chairman, Rancheria Tribal Council

The Indigenous peoples, just like the lake, faced complete erasure. There were many bands of Yokuts people that inhabited the area. Unsurprisingly, these people were vitally connected to the water and its ecology. Pah-áh-su, Pah-áh-sē, Pa’ashi - all translate roughly to "big water". The creation stories of the tribes trace back to the lake, and the water, mud, plants, and animals. First contact with Europeans was made in the late 1700s, initially by the Spanish and their Catholic California missions. However, the gold rush of the 1800s was when the large and devastating incursions occurred. Those not killed by disease were enslaved, murdered, or forcibly relocated to reservations in the mid-1800s. By the late 1800s, draining of the lake was fully underway, and largely viewed as progress by the settlers. One island in the center of the lake - “skull island” - is a mass burial site, and accounts by this time noted human bones could be seen sticking out of the island sand. It is telling that most of the early photos of this era are of farm machinery, schools and towns. The lake itself was rarely photographed, its very existence seemingly being swept into the haze of history.

By the early twentieth century, Tulare Lake no longer appeared on most maps. The fields that replaced it were productive, orderly, and legible in a specific kind of way. Since that time, agricultural activity in the former lake bed has become some of the most productive and valuable in the United States. The J.G. Boswell Company was established in 1921 and eventually became the world’s largest private farm (Arax and Wartzman 2005). Today, area farms continue to produce huge amounts of cotton, tomatoes, tree nuts, alfalfa, milk and grains.

The lake was declared dead. Except it didn’t die. Not really. The rivers never forgot where they were going. Everything still drains toward the lowest spots on the land - that ancient lakebed. And every 15 years or so, when the reservoirs are full and the atmospheric rivers do not stop, the ghost rises and the lake returns.

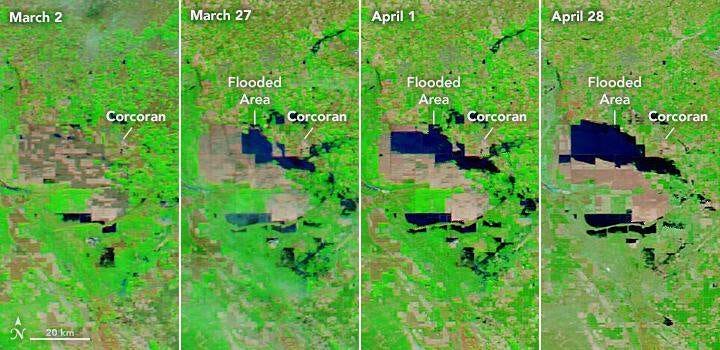

It did so most recently in 2023, spreading across the former lakebed to its largest extent in decades. Since completion of the major dams on the tributaries in 1961, the lake re-emerged in 1969, 1983, 1997, and 2023; equating to a ~7% chance of lake appearance in any given year (Lund 2023). For many, the most recent return was a total shock. Not because the flooding was unprecedented, but because the lake itself was largely unknown to California, America, and the world. Every fall, when I taught about the existence of Tulare Lake to my fish class at UC Davis, I watched the same realization spread across the faces of students. Many of these young people grew up in the Central Valley or Southern California, and never heard of Tulare Lake. And the look was always the same: disbelief, followed by something closer to horror.

The major shock is not the lake’s return, nor even its disappearance. The deeper unease rests in how something so large, powerful, and ecologically dominant could vanish that quickly and thoroughly from our cultural memory. In this way, the ghost of Tulare Lake has much more to teach us than its existence alone. Tulare Lake wasn’t drained because it failed. It was drained because it worked, precisely as nature intended. That function was powerful in its own way, just not in a form the new economy could see. America therefore sacrificed the lake for food, economic growth, and security. At the time this was seen as progress.

And in that sense, the story of Tulare Lake is not unique. Across eras and cultures, we all choose the landscapes and species we are willing to lose. And when we do, we absolve ourselves of the act, usually in the name of progress. But the natural world does not vanish cleanly. It leaves a stain. The ghost may return as subsiding soils and collapsed aquifers. As mega-floods or mega-fires that overwhelm infrastructure built for a calmer past. As fisheries that resemble the original systems, but are now dominated by invasive species. The original ecosystem is gone, yet its soul and logic persists.

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen.” ~Aldo Leopold

These are not failed ecosystems. They are sacrificial ones. Demolished, then rearranged according to a narrow vision of productivity.

Once you begin to recognize sacrificial landscapes and species, they appear everywhere. They are the tiled and filled wetlands of the Midwest, written about so passionately by Chris Jones. They are the densely fragmented rivers, choked with dams and concrete levees, written of by Jonathan Tonkin. They are the delta smelt and the broader unmaking of the San Francisco Estuary. It is the Aral Sea, drained in a manner not dissimilar from Tulare Lake. They are our urban lands, denuded and paved over, insects erased by traffic and pesticides.

Towards a new future

It would be a mistake to frame this story as one of villains and victims. The people who drained Tulare Lake were not uniquely malicious. Early producers who diverted waterways and drained wetlands were not really acting on their own ideas of “reclaiming” the Valley floor; they were responding to federal incentives that granted land ownership in exchange for clearing it. Agriculture in the Central Valley did not emerge from ignorance, but from ingenuity, individualism, a ton of really hard work; and also federal policies that incentivized the transformation.

Nor is agriculture itself some sick problem that requires redressing. With nearly eight billion people on Earth, humans must have farms, and actively manage landscapes. The Public Policy Institute of California estimates Central Valley agriculture is responsible for 340,000 jobs, and produces more than $24 billion in revenue each year (Escriva-Bou et al. 2023). We need farms, food security, and a productive economy. And we need cities where large populations can live safely and affordably. These systems must be reliable, efficient, affordable, and ethical. Retreating from management altogether is not possible nor is it desirable. In addition, every producer I meet today generally wants to do the right thing, and to find a way for people, ecosystems, and agriculture to coexist. They don’t want a future filled with ecological collapse - I learned this during seven years working on the salmon-rice project.

The challenge, then, is not whether we manage landscapes…but how? Can we learn to work with the dominant ecology rather than continually against it? Can we design systems that remain profitable, while leaving a softer footprint on the land? Can we preserve biodiversity?

I believe we can.

And Tulare Lake offers a compelling place to think about these questions. California still struggles with sufficient water storage, even as more precipitation arrives as rain rather than snow. Further, land subsidence caused by groundwater overdraft is actually deepening the lakebed every year, and fairly dramatically. The valley floor holds the memory of where the water wants to go, and all these factors are only intensifying the desire of the lake to return in ever stronger ways.

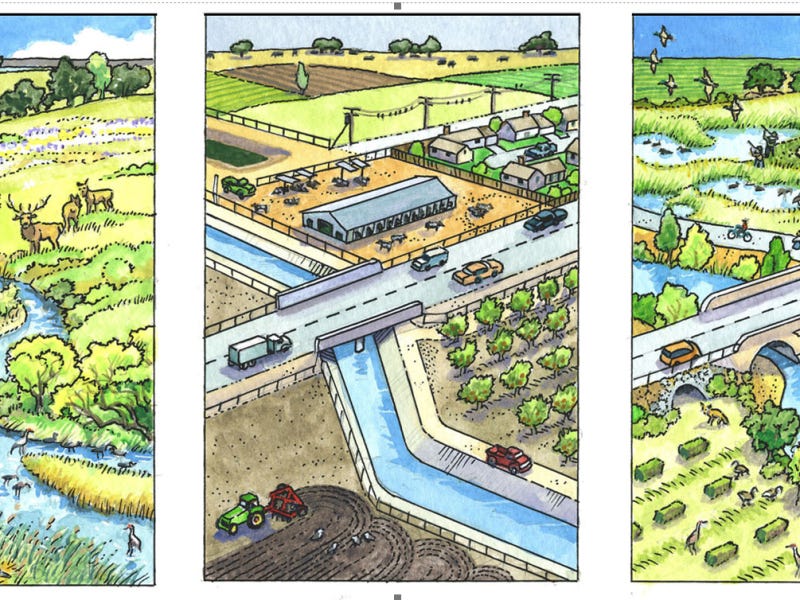

A re-imagined lake could store water when it is abundant, reduce flood risk, slowly recharge aquifers, and support ecosystems, all while continuing to serve agriculture. The lake could be flexible, right-sized, deeper possibly, highly seasonal, and fully integrated with modern agriculture and water management. Paradoxically†, California is accelerating efforts to build a new off-channel reservoir in the Sacramento River Basin for this exact same purpose (Sites Reservoir). Much of the infrastructure to move and manage Tulare water is in place. What is missing is not capacity, but imagination, political will, and trusted science-based collaboration. Oh and yes, money too. There is at least one plan afoot towards such an idea, but it is unclear how much support it has.

We do not have to manage ecosystems the same way we always have. We now possess capacity to better align agriculture, cities, and ecological function. To craft landscapes that remain productive while working with, rather than against, the grain of a land ethic. Doing so will require humility, cooperation, science, and a willingness to loosen our grip on absolute control. Total control on something so powerful was always a mirage. We need people who are not afraid to work with others that do not agree with them on every single thing. And to accept that we may not know exactly where such collaborations lead. Other lakes that experienced similar fates found their way back to us in time, e.g., Lake Mattamuskeet.

In the end, I wonder if the ghosts aren’t really curses after all. Perhaps they are warnings, and invitations. If we listen dutifully, they need not remain stains rising from the cemeteries of history to haunt us. They can instead be purposeful live systems that benefit us: things recognized, undeniable, and managed respectfully. We will know these ecosystems by their names, not because they came back, but because we finally stopped pretending they don't exist.

Go deeper

Arax, M. and R. Wartzman, 2005. The King of California: J. G. Boswell and the making of a secret American empire. Perseus Books.

Cunningham, L. 2010. A State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California. Heyday Books.

Escriva-Bou, A., E. Hanak, S. Cole, J. Medellín-Azuara. 2023. Policy brief: the future of agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley. Public Policy Institute of California.

Lund, J. 2023. Tulare Basin and Lake - 2023 and their future. California WaterBlog https://californiawaterblog.com/2023/05/07/tulare-basin-and-lake-2023-and-their-future/

Moyle, P.B. 2023. Lake Tulare (and its fishes) shall rise again. California WaterBlog https://californiawaterblog.com/2023/04/16/lake-tulare-and-its-fishes-shall-rise-again/

Preston, W.L. 1981. Vanishing Landscapes: Land and Life in the Tulare Lake Basin. University of California Press.

Rypel, A.L., D.J. Alcott, P. Buttner, A. Wampler, J. Colby, P. Saffarinia. N. Fangue, and C.A. Jeffres. 2022. Rice and salmon, what a match! https://californiawaterblog.com/2022/02/13/rice-salmon-what-a-match/

Rypel, A.L. 2023. Facing the dragon: California’s nasty ecological debts. California WaterBlog https://californiawaterblog.com/2023/06/11/facing-the-dragon-californias-nasty-ecological-debts/

Rypel, A.L. 2025. No one talks about rivers anymore. Tangled Nature https://tnature.substack.com/p/no-one-talks-about-rivers-anymore

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulare_Lake

https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2025-07-03/restoring-tulare-lake

Multimedia resources

Listening while re-reading suggestion: “O” by Coldplay (below)

The below video is a great introduction to Tachi Yokut culture in the Tulare Lake region today.

The below video is an excellent “must-see” documentary on Tulare Lake. It won’t play in window on Substack, but is clickable. The second video below is a follow-up to the first documentary that was filmed after 2023 flooding (also worth watching).

This is a Good Morning America piece filmed during the most recent flooding of Tulare Lake.

The below video is an interesting older video showing how Tulare Lake flooding periodically occurs in the area to the surprise of many.

Footnotes

†It only seems like a lot paradox. The difference between Tulare water and Sites water is that all the Tulare water is already spoken for. Sites Reservoir water is “new water” filled during wet years - the only years that still produce any numbers of salmon in the Sacramento Basin.

Amazing story...I had no idea this happened. Powerfully written piece!

Thank you... Tulare Lake has fascinated me since I was a child visiting the area ... I've heard legends and badly constructed stories... I truly appreciate this piece.